This is Part 5 of a pre-print draft of Chapter 6 from Smart Things: Ubiquitous Computing User Experience Design, my upcoming book. (Part 1) (Part 2) The final book will be different and this is no substitute for it, but it's a taste of what the book is about.

Earlier chapters in this series: Chapter 3, Chapter 1Citations to references can be found here.

Chapter 6: Information shadows

Part 5: Design with Information Shadows

Designing with information shadows means using devices, such as RFIDs, that may have specific, limited functionality and capabilities. However, as with the FedEx example, designing with information shadows often requires global service design. Information shadow user experience design must simultaneously consider (1) what happens when every object is automatically tracked and (2) how to associate those objects with all available digital information about them.A systematic approach to user experience design can reduce the possibility vertigo of multiplying two such nearly infinite sets. Despite the speed and novelty of changing technologies, people's underlying needs and desires change slowly. What has changed is that a new powerful tool is now available to address those needs.

The use of information shadows is still in its infancy, but several interesting design properties of information shadows have emerged:

- They simplify the design of certain kinds of devices.

- They allow designers to treat dedicated devices like physical embodiments of Web services and create mashups.

- They allow mass customization of experiences without mass customization of objects.

- They allow devices to be self-disclosing for disposal and recycling.

- They blur the line between devices and services.

- They create novel, pleasurable, entertaining experiences.

These are described in more detail below.

Information shadows simplify devices

When an object no longer has to display all of the human-readable metadata needed by users, its design can be simpler. The labels on bags of chocolate chips only have room for one or two recipe suggestions. Now, the chocolate chips can have their own cookbook, and the label only to point to it. Similarly, devices can be simplified down to the single thing they do best. You might want to use a pedometer to track miles walked each day for a week. The pedometer interface can be quite minimal if devices—such as a mobile phone—can access that pedometer's information shadow. The pedometer itself just needs a power button, status indicator, and walking progress display. Other devices—with larger screens and more computing power—can focus on helping users make sense of information about their exercise plans.

Physical/Network mashups

Ubicomp mashups attempt to move computation off the desktop and integrate it with the artifacts of everyday life. They extend beyond the Web and combine the functionality of both software and hardware components. (Hartmann et al, 2008)

Many Web-based services have published API (application programming interfaces) that allow other services to use their information and computational capabilities in novel ways. Google Maps, the classic of the genre, allows developers to layer information over map images that Google provides. Physical/network mashups create novel experiences that merge the power of simple, lightweight devices with the power of existing Web services.

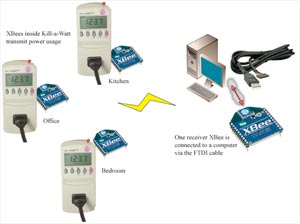

Figure 6-9. Tweet-a-watt (Fried, 2009)

Fried and Torrone's 2009 Tweet-a-Watt project (Figure 6-9) is one such mashup. It posts electricity use to Twitter, using the same API that's normally carries people's Twitter posts about their own activities. But Twitter can easily broadcast information about devices, making hour-by-hour updates about energy use accessible to humans and readable by software.

Ubicomp device user experience designers can hook up information about objects to data sources on the Internet using the same APIs and protocols used by web site mashups. [Footnote: Bleecker (2005) takes it further, and defines the term blogject to describe devices that act like people on the Internet. They can blog, they can post to Twitter, they can reply to human conversation. For Bleecker, "blogjects become first-class a-list producers of conversations in the same way that human bloggers do—by starting, maintaining and being critical attractors in conversations around topics that have relevance and meaning to others who have a stake in that discussion."] These physical/network mashups build on existing web design methods and provide a familiar set of web concepts to describe how physical objects and online information can interact.

Mass customization

The digital information shadow associated with an object is much easier to change at whim than that object's physical form. Mass customization of experiences gets much easier when the majority of the customization happens digitally. For example, the WebKinz toy line (See Chapter 7) connects toys that physically differ only slightly (like Cabbage Patch dolls of an earlier generation), but have rich online personalities.

Conversely, merging information shadows with rapid manufacturing techniques such as 3D printing allows for the instantiation of data in a physical, purchased object. Materialise, a Belgian 3D printing firm, sells a line of intricate designer lamps for the high-end furniture market (under the .MGX brand). Each lamp is individually printed. When first introduced, every lamp came with a disk containing a CAD file describing how to recreate that lamp. It's the lamp's DNA and part of its information shadow. Since Materialise keeps copies of the files, the lamps are, in effect, immortal: if a lamp is broken, they can print another one. Each lamp can be unique, or replicated as often as a buyer wants.

What happens to "mass production" when an object's physical form is based on a unique digital file? In a sense, we can now go back to a pre-Industrial Revolution era of unique objects. But now the uniqueness stems not from the imperfections and unpredictability of hand craft processes, but from a manufactured object’s relationship with its informational shadow.

Smart disposal and recycling

Because information shadows can contain any kind of information, they can contain instructions for how to dispose of the object they shadow. [Footnote: I first heard this idea in a lecture by Bruce Sterling. In Sterling (1999) he writes "Smart garbage doesn't fester in darkness, ignorance and denial. It becomes a resource."] They can self-disclose not just what information they collect and use (as per Greenfield, 2006), but how to fix, disassembled and recycle them.

For example, information about the materials from which the object is made can be mashed up with a database of municipal recycling rules to generate instructions for how to locally recycle the object. San Francisco—where I live—has an advanced recycling program that automatically distinguishes between many materials. However, I still don't know if I can put a steel car part, Styrofoam or shoes with a "recycle" logo on the sole in my plastic recycling bin. The rules of what is acceptable, and how to prepare it, change regularly. An information shadow mashup linked to each object could clarify that question instantly, directing me to take my esoteric recyclable to a specific location or to treat it in a specific way.

Similarly, complex items, such as consumer electronics or robotic toys, are difficult to recycle because they require too much disassembly and contain unknown materials. For the municipality, these objects' information shadows could contain disassembly instructions and complete materials lists. With more information, city systems could know what do to with old toys besides sending them to the dump.

Information shadows enable new kinds of services

Note: See Chapter 8 for a more general examination of this topic.

By giving objects unique identifiers, shadows allow those objects to become the subjects of services that track them and interact with them. Everyday objects can become subscription services. [Footnote: Again Sterling got here first. In Sterling (2001) he describes a furniture subscription system that creates one-off customized furniture on demand.]

In the days before the breakup of AT&T, Americans didn't own their own telephones. They leased them from the phone company. Although "Ma Bell" limited the range of phone choices, the phone company was required to repair broken equipment. The company could arrange update the whole system systematically and thoroughly, whenever it wanted. Though not ideal, the system had its benefits. It was also nearly impossible to replicate without the resources of an enormous company like AT&T. Information shadows could facilitate similar—but not so resource-intensive—for many other kinds of products and consumers.

For example, a shoe company could sell sustainable shoes by subscription. The shoe easily disassembles, yet is sturdy and comfortable. Buying the shoe means buying into a subscription for that shoe. As one part wears out, or as fashions change, the shoe can be disassembled, and mailed to a central warehouse, which mails back a replacement part. The shoe's information shadow says exactly which replacement it requires.

More directly, unique item-level identification allows for services that determine authenticity and trace provenance. In some parts of Africa, 30% of pharmaceuticals are counterfeit. mPedigree is using unique identifiers, printed under a scratch-off material, to identify authentic drugs (Schenker, 2008). Sending the number by text message to a trusted central location checks the authenticity—and then the expiration date—of the pharmaceutical. If the identification number is valid and the medicine's shelf-life has not expired, the system sends back another text message with a simple affirmation. Similarly, a purchaser can use the information shadow of a grocery item to trace its progress back to the farm where it was made and verify whether their farming practices are sustainable and humane. Similarly, an expensive designer handbag can be quickly authenticated.

The service possibilities of information shadows are enormous.

Entertainment

Once an object is identifiable and trackable, it can become a token in a game. One of the earliest such games was "Where's George?" (wheresgeorge.com), which traces the passage of one dollar bills across the world using the bills' serial numbers. Many people find it fascinating to see where the bill they're holding had been and where bills they entered into the system have gone.

That is, of course, just the tip of the iceberg. Mediamatic, a technology design organization, challenged a group of designers at the PICNIC 08 conference in Amsterdam to create social games using RFID tags that every conference participant was given (Mediamatic, 2008). After a week of hacking, the 30 people in the workshop had created ten functioning games (Table 6-1).

Table 6-1. Games developed usink ikTag RFID tags in a week of hacking by groups at the PICNIC 08 conference. The text is from a flyer printed by Mediamatic, the organizer of the hacking week.

- ikRun. Run from the conference to the PICNIC Club and record your fastest time and finishing photo. Scan your ikTag at the start next to the E-Art dome, scan again to finish and win!

- Friend Drink Station. Free drinks for new friends! Mediamatic offers a free drink and a new friendship in the network. Just swipe your ikTag and push the button.

- Department. Use the ikTag to see what the Department of Information Security & Privacy knows about you. The DISP is buying privacy and selling security.

- ikCam. Swipe your ikTag to add your portrait to your profile. Or gather up to 20 friends with ikTags and make shapshots!

- Breathalyzer. Use the ikTag, blow into the straw and test your alcohol intake. The outcome will be published on your profile. Compare your drinking skills with others at PICNIC.

- ikWin! Use your ikTag to challenge someone in a battle for Google ranking. Two scissor lifts will go up, the more hits, the higher you go.

- Mobile Massage Couch. Sit down on the two seater with a new friend, use your ikTag to get a free massage. You can win bonus time as a gift from the crowd.

- DuckRace. 2 players start their race cars with their ikTag. The race track is based on your profile and network. The audience will influence your race car with their ikTag.

- Breedrs. Drop your ikTag in the Breedrs Pond and see it evolve into a creature, with DNA based on your profile. Is this love or war?

- Vbird. Contact the Vbird with your ikTag, help it fly, meet new friends and find the interactive film in your profile.

These games represent a completely new genre of play, one that mixes physical objects (like scissor lifts, couches and breathalyzers) with online information (profiles and Google ranks) and computation. The possibilities implicit in this one week exercise are fascinating and exciting. They imply that information shadows can touch all aspects of everyday life.

Tomorrow: Chapter 3, Part 6: WineM